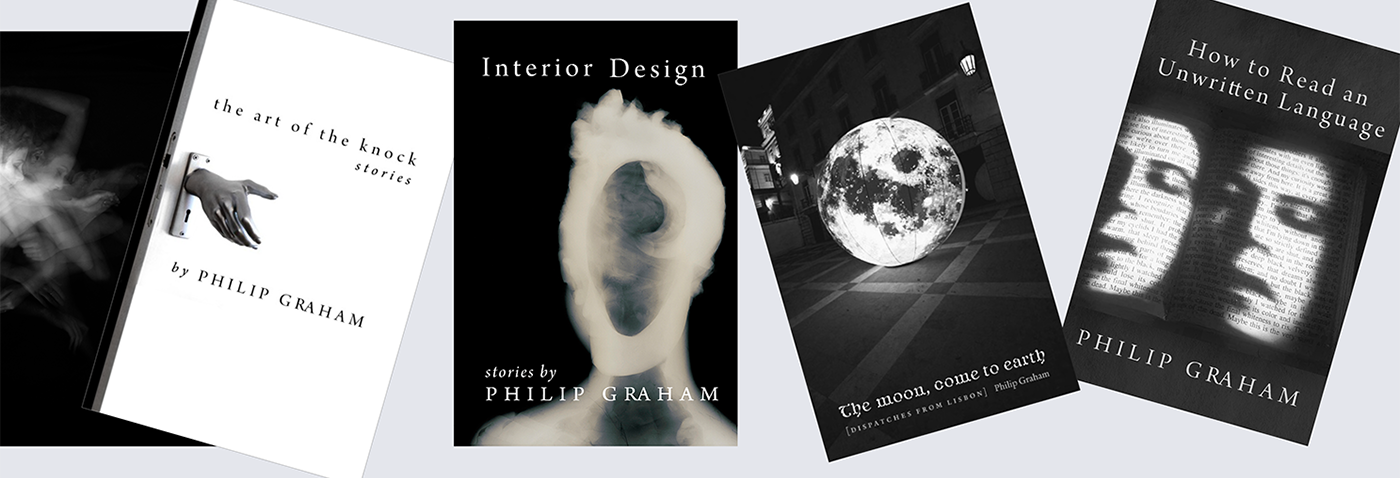

Author of eight books of fiction and nonfiction, Philip Graham has published short fiction in The New Yorker, The Washington Post Magazine, Fiction, Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere; and prose poems in The Paris Review and Virginia Quarterly Review. His nonfiction has appeared in The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, The Washington Post Magazine, McSweeney’s, and elsewhere. His books include The Art of the Knock: Stories (William Morrow), listed as one of the ten best new works of fiction of the year by the San Francisco Chronicle; Interior Design: Stories (Scribner); and the novel, How to Read an Unwritten Language (Scribner; paperback, Warner Books), long-listed for the Dublin Literary Award. These three books are available digitally in Dzanc Books’ contemporary literature reprint series, rEprint.

Author of eight books of fiction and nonfiction, Philip Graham has published short fiction in The New Yorker, The Washington Post Magazine, Fiction, Los Angeles Review, and elsewhere; and prose poems in The Paris Review and Virginia Quarterly Review. His nonfiction has appeared in The New York Times, Chicago Tribune, The Washington Post Magazine, McSweeney’s, and elsewhere. His books include The Art of the Knock: Stories (William Morrow), listed as one of the ten best new works of fiction of the year by the San Francisco Chronicle; Interior Design: Stories (Scribner); and the novel, How to Read an Unwritten Language (Scribner; paperback, Warner Books), long-listed for the Dublin Literary Award. These three books are available digitally in Dzanc Books’ contemporary literature reprint series, rEprint.

Graham’s three books of nonfiction are The Moon, Come to Earth: Dispatches from Lisbon (University of Chicago Press), an expanded edition of pieces that appeared at McSweeney’s, and in Portuguese translation as Do Lado de Cá do Mar (Editorial Presença); and two memoirs co-authored with his wife, anthropologist Alma Gottlieb—Parallel Worlds (Crown/Random House) and Braided Worlds (U Chicago Press)—which recount their experiences living among the Beng people of Côte d’Ivoire. All royalties from both memoirs are dedicated to the Beng people via the Beng Community Fund, a non-profit organization established by Gottlieb and Graham.

In 2003, Graham co-founded the award-winning literary/arts journal, Ninth Letter, for which he has served as the fiction editor or nonfiction editor, and is currently an editor-at-large for the magazine’s Featured Writer/Artist webpage. As a literary editor, Graham has devoted his career to uplifting the voices of diverse emerging literary talent from far and wide, among them Tiana Clark, Roxane Gay, Xochitl Gonzalez, Katherine Scott Nelson, Allison Parish, Isabel Ribe, Monica Romo, Thammika Songkeao, and Chika Unigwe. He has also curated digital features for Ninth Letter on trans/new-wave nonfiction, and new voices in international writing. Ninth Letter has often been cited by the annual Vida Count for its support of female and nonbinary writers.

Graham’s writing has been anthologized in The Norton Book of Ghost Stories, Turning Life into Fiction, and many other collections, and has been reprinted or translated in seven countries. His essays on the art of writing have appeared in numerous journals and anthologies.

Graham has written over 50 book reviews for Fiction Writers Review, Chicago Tribune, The Millions, and elsewhere, about the work of Chinua Achebe, Margaret Atwood, J. M. Coetzee, Nadine Gordimer, Clarice Lispector, Joyce Carol Oates, and José Saramago, among others.

His awards and honors include a National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellowship, a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, two Illinois Arts Council grants, and the Victor Turner Prize (for Parallel Worlds), as well as multiple writing residencies at MacDowell and Yaddo. He has served as a visiting writer in international residencies in Belgium, Bulgaria, China, Côte d’Ivoire, Hong Kong, Portugal, Slovenia and Switzerland.

Inspired by two superb mentors—Grace Paley (at Sarah Lawrence College) and Donald Barthelme (at the City College of New York)—Graham attempted to pay it forward at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, where he received three campus-wide teaching awards. He is now a Professor Emeritus, and Graham and his wife divide their time between Providence, Rhode Island, and Santa Fe, New Mexico.

For inquiries, contact: pg@philipgraham.net.