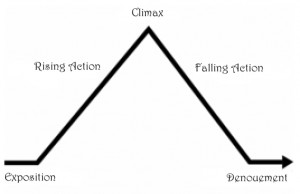

Recently, one of my students confessed to the class that in a long-ago creative writing workshop, she had once been humiliated when her instructor had chalked on the board the structure of her short story, which was found inadequate beside a comparative chalked version of the Freytag Triangle. For those unfamiliar with The Triangle, here is its basic pattern:

The chart here was originally conceived of by Gustav Freytag, appearing in a critical analysis of Greek drama he published in 1863. Since that time, The Triangle has become something of a standard in introductory creative writing texts and courses. It’s certainly easy to grasp: a narrative begins with a little expositional soft shoe, moves quickly to a rising action of tension until a dramatic climax erupts, followed by a falling action of that dramatic moment’s consequences, and finally ends with the story equivalent of sweeping out the theater after a show—the denouement.

Elegant? Yes. Instructive? Up to a point. Constricting? Absolutely.

Perhaps the best antidote to Mr. Freytag’s training-wheels triangle is a novel (one of the first in English) written in 1759, by Laurence Sterne: Tristram Shandy. The novel revels in digressions and side trips, seemingly distracted by every bright shiny thing along its circuitous narrative march. Tristram’s birth, for example, doesn’t occur until the novel’s third volume.

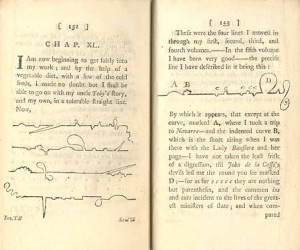

Eventually, even Tristram notes the odd course his tale has been taking, as he offers illustrations of the narrative paths of the first five volumes, each examplean inelegant and hilarious stringy thing, and each one looking as different from the others as could be.

Well, isn’t this as it should be: narrative structures like snowflakes? Best of all, I love how, with true Shandian irony, Laurence Sterne inadvertently manages to demolish a narrative theory one hundred years before it had even been thought up.

Forget Freytag, you beginning writers out there. Instead, listen to the novelist and short story writer Robert Boswell who, in an excellent interview that has recently been posted on the Fiction Writers Review website, says:

The main thing is this: I don’t want to repeat myself. I’m trying to be a literary artist. And, really, who knows what that means? But I’m pretty sure that it means at least this: you don’t settle for anything but the very best you’re capable of doing. For me, that means pushing my narratives to be different, insisting that I try something new, working to explore familiar territories in new ways, and to invent new forms each time I sit down to write.

Boswell’s remarks remind me of a marvelous video devised by two Swiss conceptual artists, Peter Fischli and David Weiss, called The Way Things Go. I once played this video for a graduate-level writing workshop, offering the opinion that it contains a wealth of narrative strategies that anyone might care to study. In a huge warehouse space, Fischli and Weiss manage to construct an odd, elaborate structure made of everyday objects that, once set in motion, takes nearly a half-hour to unwind, as principles of physics and chemistry create relentless forward motion. It could be a novel. As you can see from these four images from the film, things get busy.

The film (and its “narrative”) begins with an ominous black plastic bag bulging with who knows what sorts of secrets, building tension as it turns and turns in the air, slowly lowering, until finally it nudges a tire forward. The tire encounters an obstacle, halts, sets in motion a fulcrum that seems at first to be a reverse motion, but then that reversal pushes the tire forward again (such hesitancy on the part of that tire! Worthy, perhaps, of Hamlet’s hemming and hawing), rolling until it releases a stepladder down a soft incline.

This awkward ladder contraption in turn causes first a table and then an air mattress to fall, which drops a weighted ball from the top of a metal pole, and the attached ball slowly circles in the air, widening its path until it hits a wooden stick, which releases another black plastic bag, bulging with who knows what sorts of additional secrets, building tension as it turns and turns in the air, slowly lowering to another waiting tire, a tire that I guarantee will set in motion a whole new set of narrative strategies.

What an elegant mirroring structure can be found in the film’s first 80 seconds! The opening tension of the first twisting black bag echoed by its twin at the end of the sequence, and in between, how the pacing varies–from slow and anticipatory to sudden and violent, punctuated by hesitations and temporary reversals.

And don’t forget the thematic repetitions, how various are those tires—car tires, an inner tube, a truck tire—and how they not only serve as agents of forward motion, but also at times as a pedestal, barrier, or weight.

As the narrative strategies progress, some things will catch on fire, some explode, others will slowly wind their way to their fates. There will be another version of that weighted ball, though this one will be on fire, like some flaming comet of your nightmares. You will also encounter ghostly shoes, a knife-wielding, acid-dispensing potato, ominous chemical clouds and a glue trap, among other ingenious surprises, as well as a brief, post-apocalyptic landscape.

As the narrative strategies progress, some things will catch on fire, some explode, others will slowly wind their way to their fates. There will be another version of that weighted ball, though this one will be on fire, like some flaming comet of your nightmares. You will also encounter ghostly shoes, a knife-wielding, acid-dispensing potato, ominous chemical clouds and a glue trap, among other ingenious surprises, as well as a brief, post-apocalyptic landscape.

And through it all, a lesson repeats itself that perhaps informs characterization as much as narrative shape: that anyone’s carefully balanced equilibrium can be set awry, and what is set awry can create its own surprising pattern.

A triangle can be a wonderful thing, but geometry offers a multitude of different shapes and angles. And stories do, too. Even more so, because each story, novel or essay awaits the birth of its form, as the writer slowly hammers out its construction through the process of composition and revision. Fiction writer Diane Lefer gets the last word here—and gets it right, when she compares writers liberated from the strictures of traditional literary form to jazz musicians, in her classic craft essay, “Breaking the Rules of Story Structure”:

A jazz musician may seem to go all over the place in a musical improvisation, but there’s always an underlying structure to refer to and return to. The sense of liberating spontaneity is exhilarating when paired with technical proficiency and control.